"This is VE Day."

So starts an entry on May 8, 1945, in the diary of insurance clerk Alwyne Garling, who lived in Lexden, near Colchester, throughout the war.

Through news snippets and radio broadcasts, Alwyne updated his notes daily, giving a flavour of what life in wartime Britain was like.

The VE Day entry reads: "Churchill broadcast at 3pm and said Germans signed unconditional surrender early yesterday and hostilities cease at 12.01 tonight.

"Had holiday and went to town this morning and saw victory crowds.

"King broadcast at 9pm.

"Walked about road until past 11, looking at bonfires, searchlights etc.

"Sat up until after midnight, when the cease fire took effect."

Alwyne, who was aged 30 when war broke out, describes frequent attacks by terrifying German V-1 flying bombs and the struggle of surviving on rations.

His notes highlight how during the months following the war’s end, normal life resumed while mines began to wash up on British shores.

It is easy to think of VE Day as the start of a new era of peace and prosperity, but change, upheaval and war continued.

Alwyne followed the Allies’ progress against Japan and further fighting in the Middle East keenly.

Colchester historian Heather Johnson, who transcribed the diary entries for a family member, said: “It was good to be reminded that he did not consider the war had ended on VE Day.

“He continued to keep abreast with war news about Japan, for example the atomic bombs and mentioning VJ Day, and continued mentioning relevant events thereafter, such as the capture of Heinrich Himmler."

After his capture in late May 1945, SS leader Himmler, one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of the Holocaust, killed himself with a hidden cyanide capsule.

“Today VJ Day is often overshadowed by VE Day," added Heather.

“But it was interesting to see the emphasis Alwyne placed upon it.

“For me personally, VJ Day is just as important, because I think of all those Prisoners Of War who did and didn’t come home.

“An uncle of mine was one of the latter.”

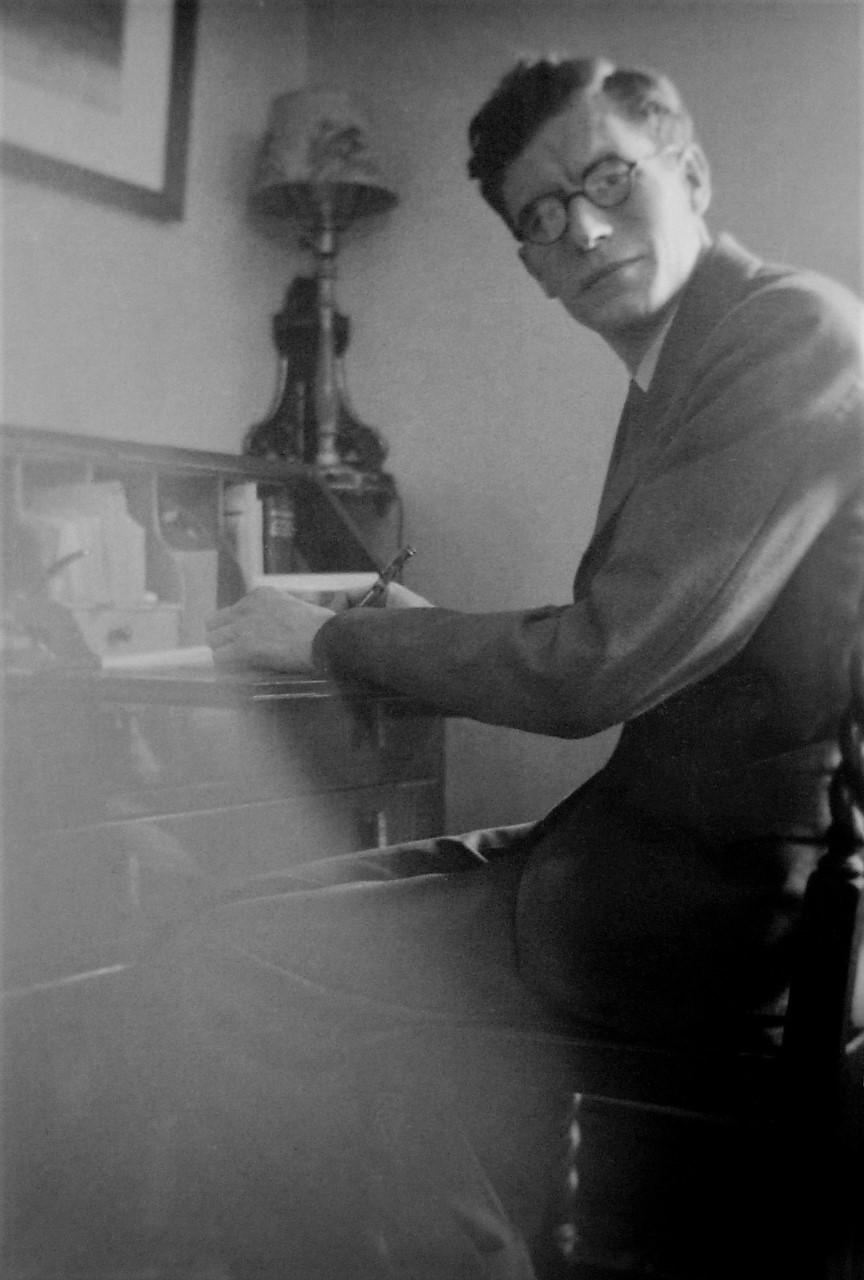

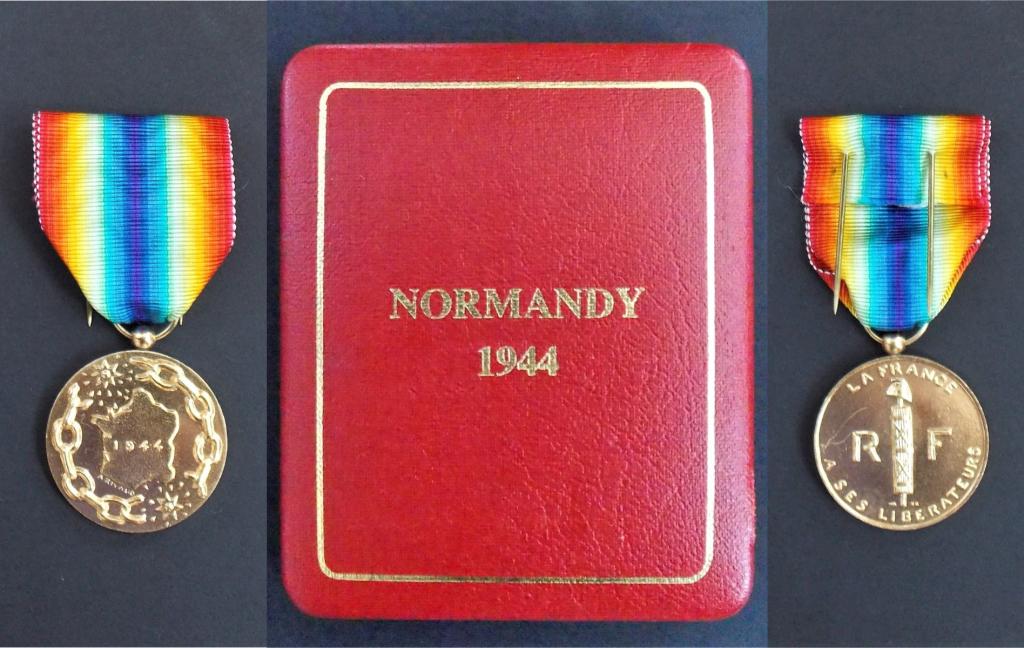

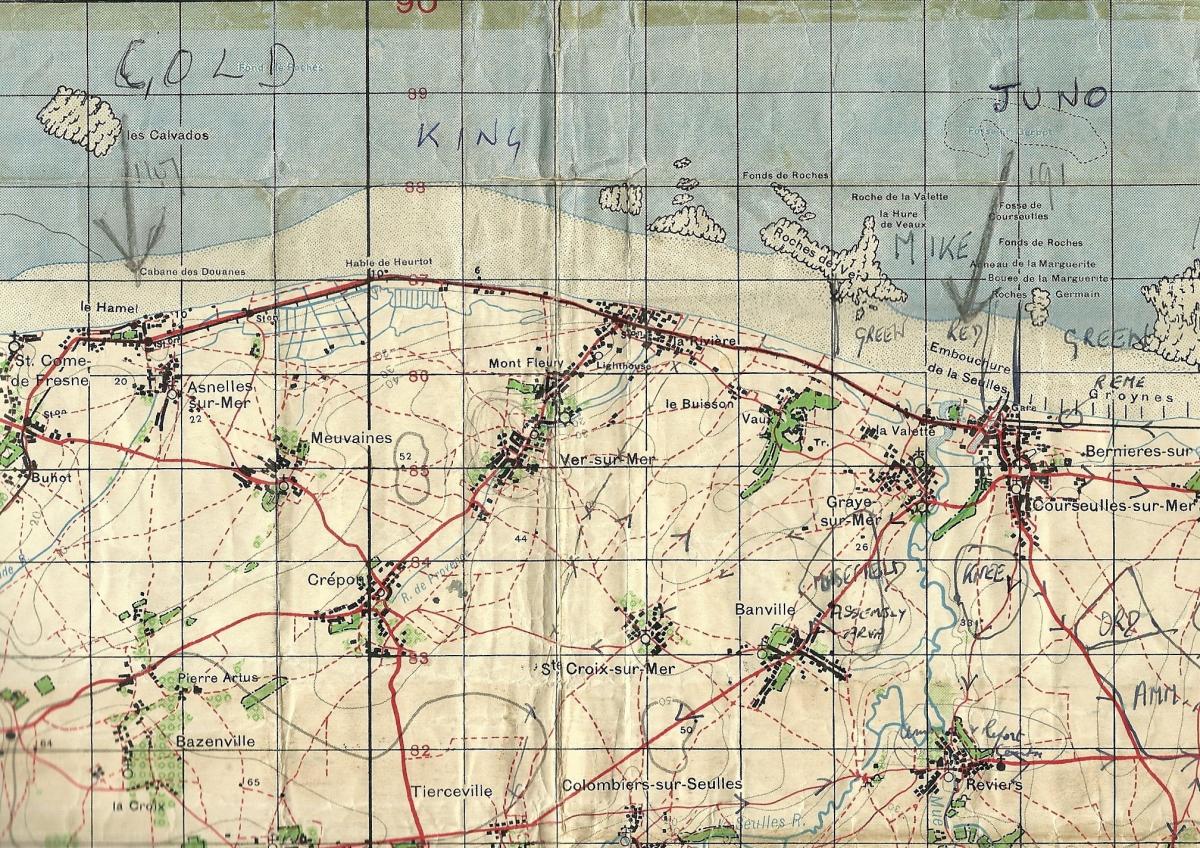

Heather’s father-in-law Felix Johnson, who died in 2013, landed at Normandy on D-Day+3 and served across Europe as part of the Royal Artillery 191st (Herts. & Essex) Yeomanry Field Regiment.

He penned his autobiography in 1994, which encompassed his six plus years of army service.

The scenes he draws from his memory paint a vivid picture of war-torn France, across which he advanced with his regiment in 1944.

It is easy to picture the liberation of European countries as a time of celebration, joy and relief.

But Felix, also from Lexden, Colchester, saw with his own eyes that occupation and oppression breed discontent.

At the commune of Doudeville, Normandy, in September 1944, Felix recalls: “We were the first troops through this part of France and they were exhilarating, heady times.

“Of course, we needed to be careful not to accept everything that was thrust into our hands.

“One of our men drank what he thought was a glass of wine, only to find he had been poisoned – no doubt by a collaborator, of whom there were quite a number.

“We saw several women who had had, or were in the process of having, their heads shaved by the French.

“They were eager to show their hatred of the women who had lived off the fat of the land while they starved.”

He also reflects on the devastation caused by the First World War while moving through old battlegrounds, counting himself lucky to be fighting a “different” war.

Felix said: “I was able to see Ypres and the Menin Gate, with its vast number of names of the men who were killed in the battles around Ypres, during the First World War.

“It made me realise how lucky I was that warfare in the second war was conducted on entirely different lines; on wheels rather than on foot; and in which the Generals appreciated the value of the men.”

With the liberation of the Dutch city of Roodendaal, the 191st Herts and Essex Yeomanry Field Regiment was disbanded and the soldiers could enjoy some downtime.

Felix grew close to a Belgian family in Antwerp, before he was recalled as a Battery Quartermaster Sergeant to assist with the Allied advance through Germany.

At a German airbase in Rheine, he recalls: "On arriving at the airport I was dismayed to see the accommodation we had to live in.

"It had been occupied by the slave labourers imported into Germany, foreigners who had been forced to work in terrible conditions.

"Everywhere had to be fumigated before it would be used.

"A few days after we arrived the Armistice was signed, and the only time the guns were fired was on V.E. Day when we gave a glorious searchlight and Ack-ack display, firing a quantity of ammunition in celebration."

He added: “Demobilisation was now uppermost in my mind.

"All personnel in the Forces had been given a group number, related to their age and length of service.

"Mine was 24.

"Many of the younger men, in group 27 and above, were posted for service in the Far East after the war ended in Europe.

"I was glad I didn’t have to go there, even though it transpired that the war with Japan would be over before they would have to go into action."

But the war, and Felix’s service, did not truly end until he was demobilised from the Army in January 1946.

Even then, soldiers were not typically celebrating, they were worrying about what came next.

“After six years and four months of full-time service it was not easy to adapt to civilian life again,” said Felix.

“I had married in 1942.

“In almost four years of married life our total time together amounted to no more than three months.”

He added: “On my last leave, before I was demobilised on January 3rd 1946, we inspected houses under construction in Colchester, as I knew I would have to return to my former employment at the Town Hall.

“All private houses then being built were regulated, and could only be sold to returning members of the Forces.

“This was decreed by the Labour government, which was very helpful to us.

“Price was also limited to a maximum of £1,200 for a house, which was also restricted to a maximum floor area of 1,000 sq ft.

“We settled on Number 23, All Saints Avenue, about to be built by W.A. Hills and Sons.”

Felix went on to become joint treasurer of the Colchester branch of the Essex Yeomanry Association, in turn holding the posts of secretary, chairman and president.

He returned to work at Colchester Council, retiring in 1979 as assistant borough treasurer.

His hobbies included oil painting, enjoying art classes and visiting his beach hut on Mersea Island.

Heather described Felix as an "honest and religious" man, who was "eager to go to war, to fight fascism."

He carried a piece of shrapnel, a result of a shell blast in France, in his body for the rest of his life.

Heather reflects on the significance of VE Day for the Western world.

"I have researched the history of my various families for years now," she said.

"As a result, I hold the strong belief that to understand the present, you have to know the past.

"Many people on VE Day must have naturally felt the war was over for them personally, because the enemy in Europe had been defeated and that was close to home geographically.

"It was an end to hostilities in Europe and the many documented atrocities that occurred during it.

"In all the occupied European countries, the atmosphere must have been even more euphoric."

She added: "My father had a much younger brother in the R.A.F. Volunteer Reserve, who had been captured at Singapore and taken as a Japanese POW.

"He was killed during one of the many recorded atrocities.

"I am reflective about this intermediary period, because the families of Far East POWs were continuing to worry about whether their loved ones were still alive.

"That was what I did hear my parents talk about.

"So, for those families, VE Day was bitter-sweet.

"Personally, I think both days should be given equal reference."

Heather's publication of her father-in-law's wartime memories can be studied at worldwartwomemoriesofayeoman.home.blog.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here